Last week at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Ophthalmology, researchers announced that the procedure, abbreviated as CK, restored normal vision in 93 percent of patients over the two years of study.

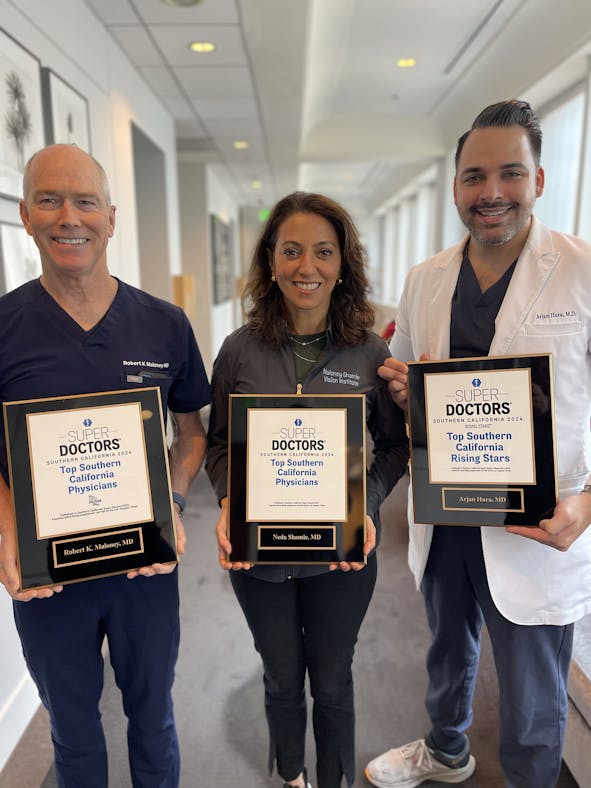

“This is really a baby boomer eye surgery,” says Robert Maloney, a Los Angeles ophthalmologist and one of the 54 doctors who tested the treatment during Food and Drug Administration trials. About 350 additional U.S. physicians will get training in the technique by spring, according to Refractec Inc., the company that makes the CK system.

Tiny adjustment, big change. Farsightedness is the result of an eyeball that’s too short or a cornea that’s not curved enough. Both lead to the improper focusing of light on the retina, causing close objects to appear fuzzy. In CK, after applying a numbing eyedrop, a doctor inserts tiny metal probes around the cornea, going just 1/50th of an inch deep. Heat sent through the probes cinches the corneal tissue, increasing it’s curve.

Bill Halvorsen, 54, a retired police sergeant from Las Vegas, says he “was tired of having glasses all over the place.” Maloney performed CK, and a few minutes later asked Halvorsen to read the time on his watch. “For the first time ever I could read all the little writing on it.”

The key is what happens to people like Halvorsen even beyond two years, says Mark Speaker, an ophthalmologist with the New York Eye and Ear Infirmary who is gearing up to offer CK to his patients. “It will take more time to really say that the outcomes are as good as those with LASIK.” The best candidates are those who were either born farsighted or developed the condition with age, are age over 40, and whose eyeglass prescriptions has changed little for at least 12 months. And like LASIK, CK isn’t covered by insurance companies. So the biggest discomfort might be the price—Maloney charges $2,450 per eye. At least patients can sign their checks without rooting around for glasses.